We are seeing an incremental spreading of devices able to collect and use personal data. Many types of services such as personalized assistance, healthcare solutions and smart cities rely on personal data for the improvement of the service. The management of personal data allows services provider to add value within the system and design practice needs to understand and consider the impacts that personal information can have on the individual in terms of changes on personal awareness, on actions the individuals perform, on relationships with other individuals, and on individual agency in the society. Personal data is now a matter of design for product and service in order to push forward the technology advancement avoiding serious consequences. We need to design services in a conscious way considering possible issues related to the use and sharing of personal information while exploiting the value that this information can have in the services. My 5 cents here is the description of the individual and social impacts of the use of personal information in connected services.

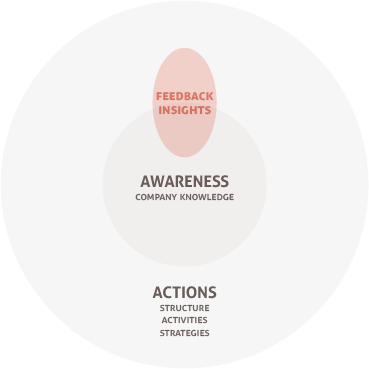

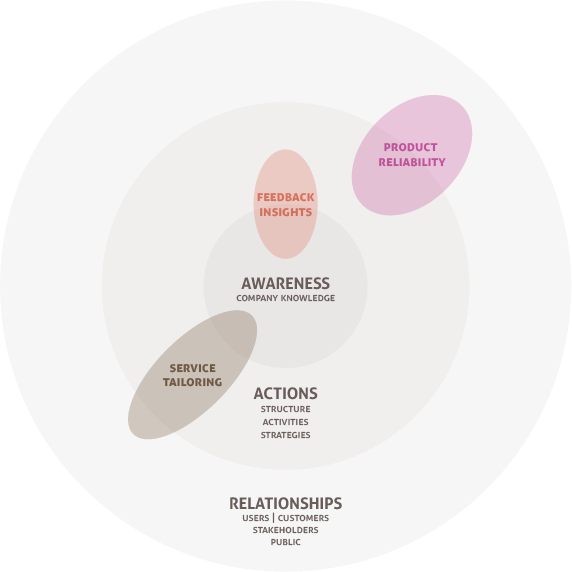

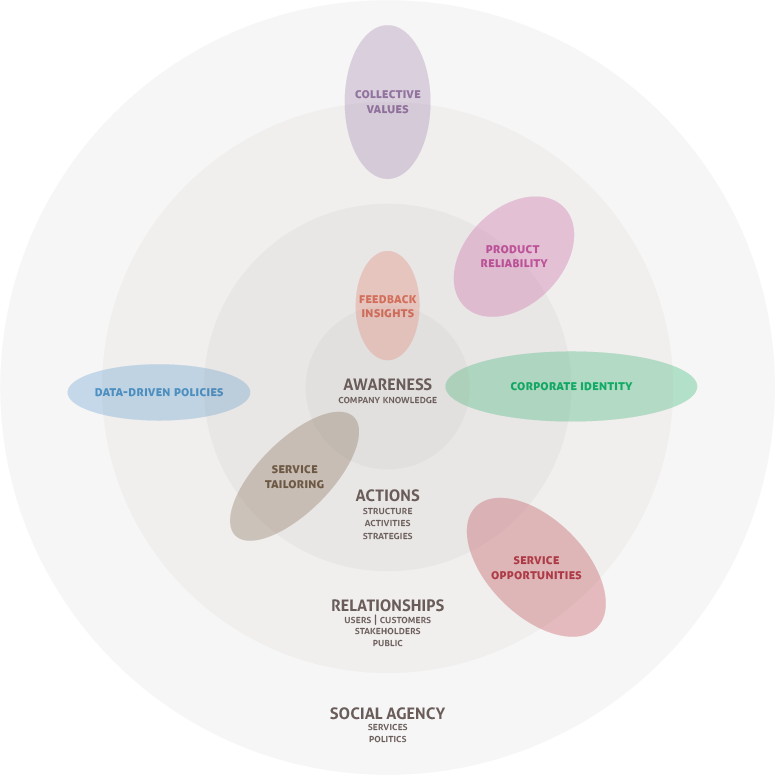

Data Impact Layers

Defining the different layers of impact of the use of personal information on individuals and society.

Year

2018

Reference Lab

IEX Design Lab

Self awarenss

In personalized services the users receive feedback from the service it in the form of visualization of real-time and historical monitoring, patterns and anomalies, personalized goals and automatic setting, notification and alerts thanks to the automatic evaluation based on comparison to references, standard or average.

The feedback impacts of the individuals self-perception altering the way they feel about themselves, the way they perceive their identity and increase self-knowledge.

Active or passive self-tracking allow users to increase self-awareness about their behaviors, activities, performances, and body parameter and health status creating self-mirroring in the provided information. While increasing the knowledge, the visualization of historical data, real-time status as well as possible projections of future trends thanks to AI predictions allows an effortless and seamless monitoring that perturb the self possibly in positive and negative ways.

Especially for medical feedback, the way information is automatically return to the user as well as its amount is a critical matter.

According to self-perception theory, the returned feedback implicitly reflect the individual perception as a result of personal self-observable behavior. In glucose level monitoring systems for diabetic people, for example, the return of information about real-time or historical glucose level has to be consistent with the user ability to understand it and at the same time has to consider emotional aspect of diabetic people so to avoid unnecessary distress. Patients with diabetes have depressive and anxiety symptoms, such more than general population due to psychological factors such as coping and locus of control. The act of being aware of some knowledge has a sort of placebo effect on the individual. The practice of profiling individuals such as in the case of behavioral targeting and social labeling for marketing also alter the awareness of individuals. Considering that people are labeled according to their behaviors, beliefs or personality, by receiving a targeted advertising the individuals project themselves in the type of persons the ad is directed to, perceiving themselves according to an external source.

Performance of actions

Proactive services lower the load on humans in making decision triggering actions according to the understanding extracted from computed data. The interaction between the user and the service, mediated by personal information, enables faster,

tailored and meaningful tasks completion and service functions. Biodata such as fingerprints and face recognition empower current fast and seamless authentications for unlocking smartphones, for digital payments and for fast access to services. Furthermore, user’s information can enable useful and meaningful micro-interactions such as the use of face proximity recognition for automatic adjustments of tones’ and audios’ volume in order to be less invasive when the user’s ears are close to the phone.

The eliciting of self-awareness through returning information and feedback also has an agency on people actions and behaviors.

The mechanisms related to behavior change such as the feedback-loop are supported and empowered by the monitoring of actions and activities. Altering the user’s awareness about status and performances, the visualization of information sets the bases for modifications in the actions performed through the creation of self-understanding. Then the user reacts to this understanding and to the engagement provided by action triggers such as goal settings and personalized experience and tailored suggestions. The result of this engagement is a change in the single actions performed and even in whole behaviors and attitudes. By logging data about food eating and even by automatic detection of food intake, users can monitor and develop self-understanding about their own lifestyle and modify their eating behaviors according to the information received.

The more types of different data are considered for the elaboration of feedback, the more complex and accurate the tailored experience can be.

If the user tracks eating habit together with exercises and performed activities, and the related health parameters, a comprehensive service is able to offer tailored suggestions or nudging to improve behaviors toward a better lifestyle. Considering personalized advertising not only for its impact on self-awareness as a mirror of the identity but also on the point of view of the changes in performance of actions, it has been invented so to have an impact on purchase behaviors way more than un-targeted advertising.

Interpersonal relationships

Considering that the convergence of social physical and virtual spheres of human life has boosted a transformation on the interaction of individuals with their environment, we can extend the concept to the interaction between individuals that inhabit this environment being it physical, digital, augmented or intelligent ambients.

By sharing information within the Internet or among users that take part to the same digital community, individuals can alter their own public images and acquire knowledge about other people.

These public images are made out of personal information creating an extended self that multiplies virtual identities and data doppelgängers adapting to the type of service (professional network, health monitoring, recreative network, and so on) and according to the community where the interaction takes place. The data doppelgängers affect the perception that individuals have each other perturbing the interpersonal relationship that occurs among the close circle (family, close friends, relatives, partners and other individuals significantly close to the user in an intimate relationship), the trusted network (friends, acquaintances, colleagues, and other people in which the user trusts at different levels and for different purposes), and among professionals (doctors, employers and employees, and other people with whom the user has a more formal relationship).

Thanks to ubiquitous connected services, knowing people through personal data is today easier than before.

As an example, on online dating platforms, people represent themselves to find personal matching. They can meet, chat and know each other through their online personal representations with a very intimate purpose. Personal information is now broadly used also to provide professional services that rely on technologies and connectivity. Data and information about people, impacts on the relationships people have with doctors, insurers, employers and many other professionals changing the paradigms of entire services. Digital care services and genome analysis, enable new types of interaction between doctors and patients. Doctors no longer have to see the patients in person, they can remotely review patient’s record and monitor parameters. Moreover, patients can access personalized healthcare services according to their information and receive tailored assistance directly from automatic systems. In the case of personal medicine as well as for online dating, however, the provider has to consider that, even if the solution facilitates and supports the service, the personal and physical interaction has a high psychological involvement that could not be properly transferred in the digital remote interaction.

Social agency

From active commitment to passive data providing, information about people impacts on their societal contribution in both conscious and unconscious ways. Personal data pass through behavioral analysis, pattern recognition, real-time monitoring and aggregated data analysis to extract information of all sorts aiming at shaping the society and the environment the people live in. Collective values shared among the society reinforce users’ willing to disclose their data for societal improvements fostering public participation in publicly sharing their personal data for the greater good. The voluntary donation of health information such as EMR and genome analyses can contribute in terms of source of knowledge for medical and pharmaceutical research.

The impact that the use of personal information has on the personal societal contribution applies not only to medical research, but also to people’s participation in the society as citizen and actors of their community.

In modern cities, people are nodes of the augmented infrastructures. Their actions, reaction and proaction shape the surrounding environment of ubiquitous connected systems of sensors and actuators. Municipalities, private and public companies, and independent entities create urban services, neighborhood, and entire cities that are designed, organized and built starting from data collected from citizen in a mutual exchange of services and social values. The social and infrastructural environments act and react according to their inhabitants and connected services take advantage of people’s information to improve and adapt according to historical data and real-time monitoring. The approach of smart cities built ‘from the internet up’, needs constant stream of data to provide reactive and proactive public services and all the decision are made according to the received information.

The use of personal information for societal purpose applies also to social policies safety justice and law making.

Artificial Intelligence can analyze surveillance cameras’ footage in real-time to extract valuable metadata aiming at improving traffic monitoring, capacity planning at shipping ports, and even detecting and reacting to emergencies. AI, as an interpreter of people’s records, is now broadly used in USA as a decision-making supporter for justice and safety impacting on people’s freedom. In order to gather data for social purposes, people are so constantly monitored, even without having a real consciousness of the different moments of tracking and sharing of their data, and of the consequences that their contribution in terms of personal information will have in the societal organization. People’s preferences, historical activities, real-time and everyday data are collected to shape service experience and to create personalized contents. These filtering of experiences and contents provided by services, impacts on the user’s representation of the external world and so on their societal perception.

Further readings

-

Aranzabal, R., Ariza, P., Fuentetaja, G., Simon, Z., & Franco, L. (2013). A time sensitive classification of tourism-related mobile applications. 11

-

Bem, D. J. (1972). Self-Perception Theory. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 1–62). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065- 2601(08)60024-6

-

Chourabi, H., Nam, T., Walker, S., Gil-Garcia, J. R., Mellouli, S., Nahon, K., Pardo, T. A., & Scholl, H. J. (2012). Understanding Smart Cities: An Integrative Framework. 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2289–2297. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2012.615

-

Frost, J. H., & Massagli, M. P. (2008). Social Uses of Personal Health Information Within PatientsLikeMe, an Online Patient Community: What Can Happen When Patients Have Access to One Another’s Data. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 10(3), e15. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1053

-

Frost, J., Okun, S., Vaughan, T., Heywood, J., & Wicks, P. (2011). Patient-reported Outcomes as a Source of Evidence in Off-Label Prescribing: Analysis of Data From PatientsLikeMe. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(1), e6. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1643

-

Goodchild, M. F. (2007). Citizens as sensors: The world of Volunteered Geography. GeoJournal, 69(4), 211–221 Gunnarsdóttir, K., & Arribas-Ayllon, M. (2015). Ambient intelligence: A narrative in search of users. http://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/74291/

-

Li, I., Dey, A. K., & Forlizzi, J. (2011). Understanding my data, myself: Supporting selfreflection with ubicomp technologies. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing – UbiComp ’11, 405. https://doi.org/10.1145/2030112.2030166

-

Lupton, D. (2013). The digitally engaged patient: Self-monitoring and self-care in the digital health era. Social Theory & Health, 11(3), 256–270. https://doi.org/10.1057/sth.2013.10

-

Mitchell, W. J. (2010). Me++: The cyborg self and the networked city. MIT

-

Mućko, P., Kokoszka, A., & Skłodowska, Z. (2005). The comparison of coping styles, occurrence of depressive and anxiety symptoms, and locus of control among patients with diabetes type 1 and type 2. 10.

-

Neff, G., & Nafus, D. (2016). Self-tracking. The MIT Press

-

Ratti, C. (2010). The senseable city. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference and Exhibition on Computing for Geospatial Research & Application – COM.Geo ’10, 1. https://doi.org/10.1145/1823854.1823857

-

Summers, C. A., Smith, R. W., & Reczek, R. W. (2016). An Audience of One: Behaviorally Targeted Ads as Implied Social Labels. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(1), 156–178. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw012

-

Turnwald, B. P., Goyer, J. P., Boles, D. Z., Silder, A., Delp, S. L., & Crum, A. J. (2019). Learning one’s genetic risk changes physiology independent of actual genetic risk. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018- 0483-4

-

Varisco, L. (2020). Personal Interaction Design: Introducing the discussion on the consequences of the use of personal information in the design process. In Mariani I., Rampino, L. Design research in the digital era: opportunities and implications. Notes on doctoral research 2020. Franco Angeli Milano (Italy) ISBN: 9788835100317

-

Weitzman, E. R., Kaci, L., & Mandl, K. D. (2010). Sharing Medical Data for Health Research: The Early Personal Health Record Experience. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12(2), e14. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1356